The moment of inertia \(I\) of a rigid body with respect to a specific axis is defined as

\begin{equation}I=\int r^2dm

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=\int r^2dm \tag{1}\\

\end{align*}

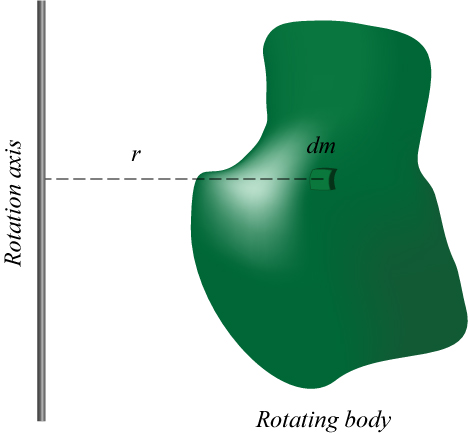

where \(r\) is the perpendicular distance of the element of mass \(dm\) to the axis, as shown in Figure 1. The moment of inertia measures the ‘resistance’ of a body to change its state of rotational motion. The moment of inertia is intimately linked to the definition of angular moment of a rigid body: For a rigid body rotating with angular velocity \(\omega\) about a fixed axis, the angular momentum is \(L=I\omega\).

The definition given in Eq.(1) is the generalization to extended bodies of the definition for a single mass point. For a mass point, we have \(I=mr^2\), where \(m\) is the mass of the particle. For a set of mass points, we will have a finite sum instead of an integral.

It is a convention to write \(I_0\) to indicate the moment of inertia with respect to an axis passing through the center of mass of the rotating rigid body.

Moment of inertia of a uniform and thin rod of mass \(M\) and length \(L\)

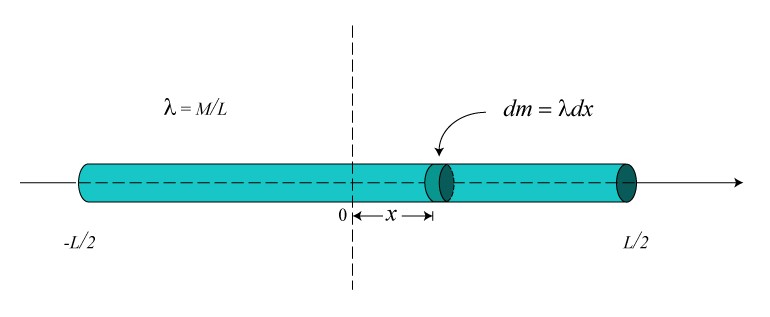

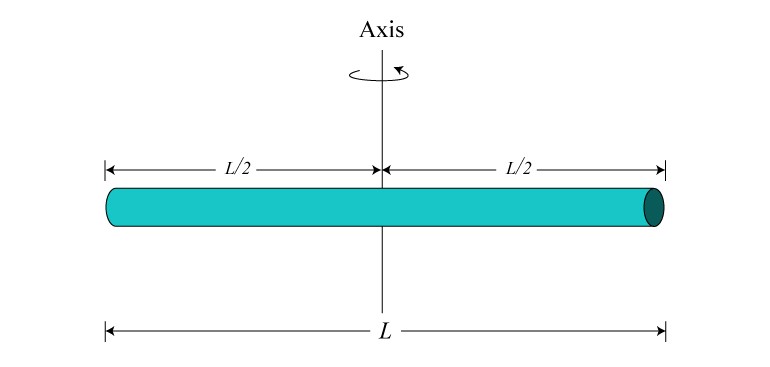

The linear density \(\lambda\) of the rod is \(\lambda=M/L\). The differential of mass \(dm\) is given by \(dm=\lambda dx=(M/L)dx\). Therefore, the moment of inertia \(I_0\) of the rod with respect to an axis perpendicular to the rod and passing through its center of mass is:

\begin{equation}I_0=\int_{-L/2}^{L/2}x^2dm=(M/L)\int_{-L/2}^{L/2}x^2dx=\frac{1}{12}ML^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=\int_{-L/2}^{L/2}x^2dm \\

&=(M/L)\int_{-L/2}^{L/2}x^2dx \tag{2}\\

&=\frac{1}{12}ML^2

\end{align*}

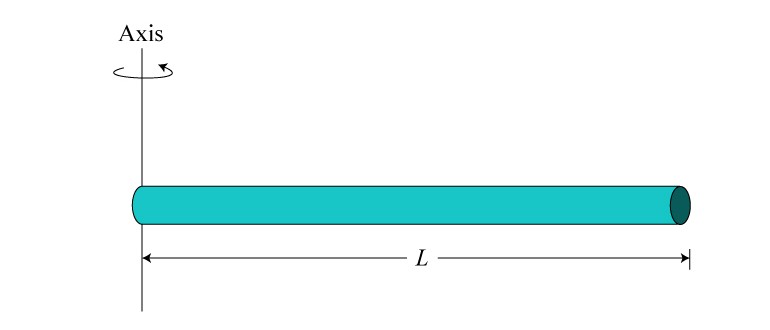

Notice that in order to calculate the moment of inertia, we simply have to put the origin of the coordinate system just at the location of the axis. The moment of inertia \(I\) with respect to an axis perpendicular to the rod and passing through an end can be calculated directly from the definition

\begin{equation}I=\int_{0}^{L}x^2dm=(M/L)\int_{0}^{L}x^2dx=\frac{1}{3}ML^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=\int_{0}^{L}x^2dm \\

&=(M/L)\int_{0}^{L}x^2dx \tag{3}\\

&=\frac{1}{3}ML^2

\end{align*}

or by using the parallel axis theorem (Steiner’s theorem)

\begin{equation}I=I_0+M(L/2)^2=\frac{1}{12}ML^2+\frac{1}{4}ML^2=\frac{1}{3}ML^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}

I&=I_0+M(L/2)^2 \\

&=\frac{1}{12}ML^2+\frac{1}{4}ML^2 \tag{4}\\

&=\frac{1}{3}ML^2

\end{align*}

How thin the rod must be?

Actually the rod has to be ‘infinitely thin’. In other words, the rod has to be a geometric line, a truly one-dimensional line. Therefore, the calculations shown here give only an approximation. Such approximation will be good whenever the rod does not differ so much of being a thin wire. The geometric form of the cross section of the rod is not relevant. Thus the approximation is valid also for a stick whenever the stick is ‘thin enough’.

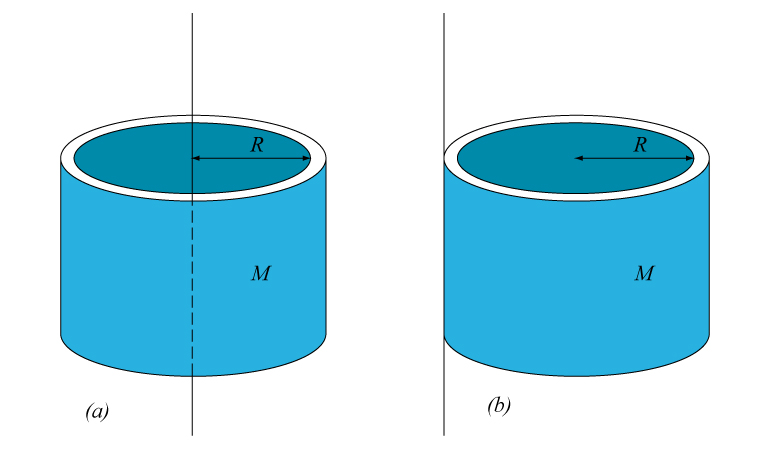

Moment of inertia of a uniform cylindrical shell of mass \(M\) and radius \(R\)

Clearly all the elements of mass are at the same distance from the axis of symmetry. Therefore, the radius \(R\) in the integral defining the moment of inertia is a constant. The result is

\begin{equation}I_0=\int R^2dm=R^2\int dm=MR^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=\int R^2dm \\

&=R^2\int dm \tag{5}\\

&=MR^2

\end{align*}

The moment of inertia with respect to an axis lying on the surface of the shell and parallel to the axis of symmetry can be calculated by using the Steiner’s theorem:

\begin{equation}I=I_0+MR^2=2MR^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=I_0+MR^2 \\

&=2MR^2 \tag{6}\\

\end{align*}

The shell has to be thin in order for these calculations to be a good approximation. Because of the symmetry, the height of the shell is not relevant. This means that two shells with identical mass and radius, but one being larger than the other, will have the same moment of inertia.

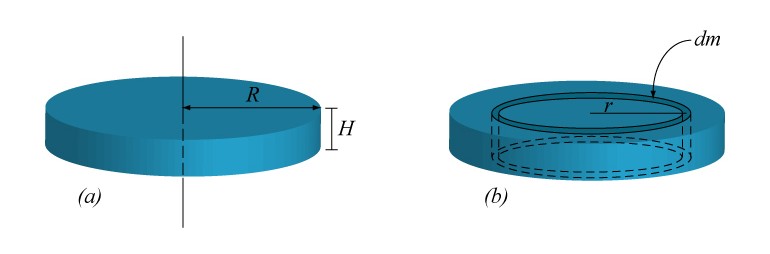

Moment of inertia of a uniform cylinder of mass \(M\) and radius \(R\)

Suppose that the cylinder has height \(H\). Due to the symmetry, we can consider elements of mass which have the form of cylindrical shells of radius \(r\) for \(0\leq r\leq R\). The density of the cylinder is \(\rho=M/(\pi R^2H)\). Thus, \(dm=\rho H2\pi rdr=(2M/R^2)rdr\). Therefore:

\begin{equation}I_0=\int_0^Rr^2dm=(2M/R^2)\int_0^Rr^3dr=\frac{1}{2}MR^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=\int_0^Rr^2dm \\

&=(2M/R^2)\int_0^Rr^3dr \tag{7}\\

&=\frac{1}{2}MR^2

\end{align*}

We note that the height \(H\) is not relevant due to the symmetry. The moment of inertia with respect to an axis parallel to the axis of symmetry and passing through the border of the cylinder can be calculated by using the Steiner’s theorem:

\begin{equation}I=I_0+MR^2=\frac{3}{2}MR^2

\end{equation}

\begin{align*}I&=I_0+MR^2 \\

&=\frac{3}{2}MR^2 \tag{8}\\

\end{align*}

Leave a comment